After our last school year, I’ve learned that simplicity in teaching is key. When our instructional methods are simple, we can focus on the beautiful students in front of us. I want to share six questions that guide my approach to teaching writing. No matter what writing curriculum you use, reflecting on these questions now will help you set your writing instruction on a smooth course for the months ahead.

1. Does my writing curriculum emphasize purpose?

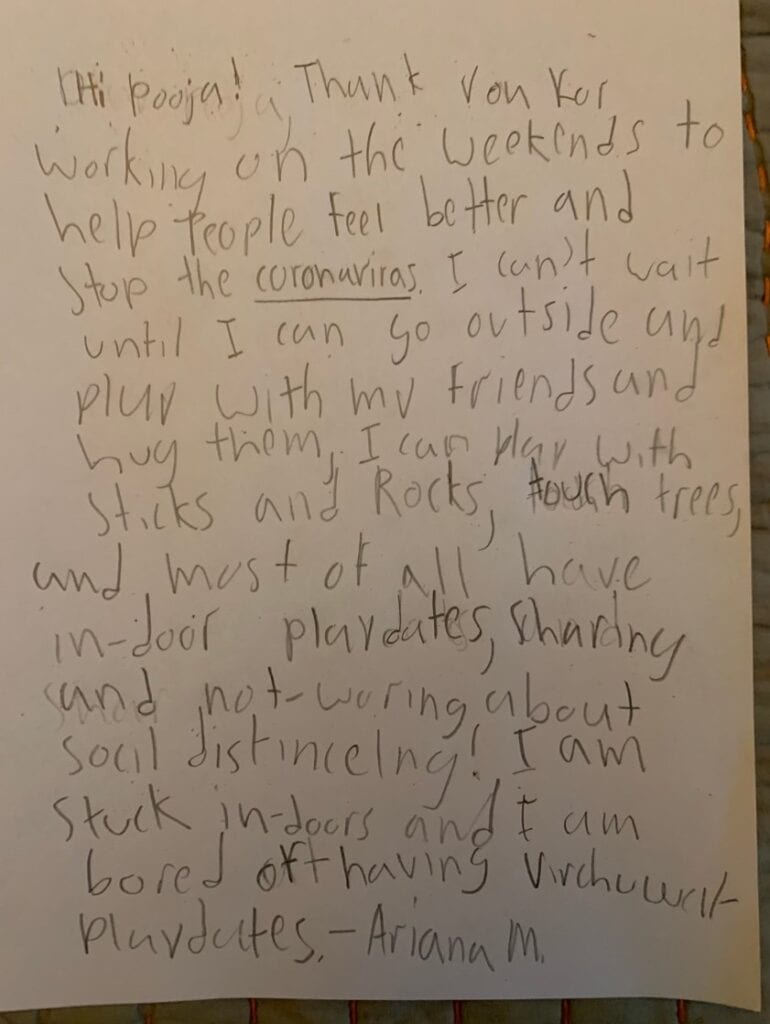

It can be helpful to look over your current writing curriculum to ensure that the lessons you have planned give students purpose for their writing or help them uncover their own purposes. When children understand why they are writing and who they are writing for, they have a purpose. As a result, they are far more motivated and engaged in the writing process. Last year when the pandemic struck, my daughter and I were both left feeling anxious and lost. My daughter found her way forward when she decided to write a letter to an ER doctor thanking her for her service. The minute she put pencil to paper, an expression of calm resolve came over her face. Purpose-driven writing creates the conditions for skill and craft to flourish.

The why for writing can be audience-driven as it was in the above example, but sometimes the purpose for writing can be driven by what skills or strategies students are trying to practice. For example, when students understand they are writing a particular sentence using sensory-rich language, or chooses to write a story as a way to get better at dialogue, they go into the endeavor with a clear purpose. No matter what the exact purpose is, it is essential that students know the why behind the writing they are doing.

[contextly_auto_sidebar]

2. Does my curriculum emphasize high-quality topics?

When I first started teaching, I assumed that children should always choose their own topics. Because of that, I never got involved with that part of the writing process. I let them write about whatever they wanted, even if I had some apprehension about whether they could write well about the topic they had chosen. What I realized over time is that students write best when they are writing about:

- A topic they know well.

- A topic they are passionate about.

- Topics they are curious and/or are yearning to learn more about.

Helping students write about a high-quality topic can/should play out in different ways in the classroom. At times it might mean that a child chooses a personal topic from their own lives. For example, a student might choose to write a persuasive essay trying to convince teachers to give only half an hour of homework per night. A student would choose that topic because he is passionate about that idea. His passion for that topic would help him write well and perhaps would encourage him to do some further research. Other times, writing about a high-quality topic might mean that children are writing about what they are learning in school. For example, a second-grade class might be learning about different buildings in New York City. Once children have become knowledgeable about the buildings, the teacher could ask her students to choose one of these buildings and write an informational essay teaching other students about what they had learned.

Take some time to look at your current writing curriculum. Are children writing about topics they know well? Do they have opportunities to choose their own topics? Are they also asked to write about topics they are learning about in school? Use these questions to reflect and revise your writing curriculum.

3. Is my writing curriculum joyful?

Writing time in classrooms should be joyful because our students deserve nothing less. A recent study spoke about how a person’s mood can influence how well they comprehend a text —the better their mood was, the better their comprehension. Although this study was about reading, the same is true for writing. Ralph Fletcher, in his book Joy Write, says it best: “Play in writing is not just a nice idea—it’s essential. It’s that playfulness that brings a sense of joy to our teaching and to our students’ learning.” Of course, there are always moments of difficulty in writing. That is how all writers grow. Nevertheless, if the overall feeling in a classroom is that of playfulness and joy, children can more easily navigate the harder parts when they arise.

You might want to take a joy inventory during your writing instruction. Is there a playful spirit to how you teach writing? If not, are there small tweaks you can do to make your writing instruction more joyful?

4. Does my curriculum address all aspects of learning to write?

In my early days of teaching writing, I focused almost exclusively on the craft of writing and left the conventions of writing to bubble up organically. Frankly, that was a rookie mistake. A strong writing curriculum gives all students equal access to all parts of writing instruction—including conventions. I find it helpful to divide the parts of learning to write well into three main categories. Teachers should provide instruction within each of these categories:

- Language conventions (spelling phonics, handwriting, punctuation).

- Language composition (vocabulary, grammar, sentence structure, genre).

- Application (how to apply both language conventions and language composition while going through the writing process).

I would suggest taking some time to look at the writing lessons provided in your curriculum. Are all three of these categories given equal access? If not, how can you fill in those gaps?

5. Is my writing curriculum flexible?

Although there are skills that we will teach our entire class, every child’s path to learning that skill will be different. Some will need lots of practice and your support. Others will not only need you to share the work with them, but they will also need you to guide them as they try it on their own. Still others will need further support as they try to apply that skill/strategy to a new topic. The tricky part is that other students will need very little practice. You give them a little bit of “we do” instruction and they are ready to roll. No matter what curriculum you are using, you want to have the flexibility to tailor your instruction so that each student gets the type of practice they need.

Are there opportunities for you in your curriculum to give students the type of “we do” practice they need? If not, what types of revisions can you make so that you can be more flexible?

6. Is my end goal student independence?

One important aspect of quality instruction is that students get supported practice, as I described above. It is imperative not to forget that you are giving them this supported practice so that they can eventually do the same work on their own. There are many ways to emphasize independence, from classroom routines to meaningful practice to deliberate language, but probably the most important thing is to give students time to write independently every week. In that way, you can use your formative assessments to see when they reach independence with the skills and strategies you are teaching.

Does your writing curriculum make time for independent writing? If it doesn’t, you might want to carve out some time each week for your students to write independently.

Writing instruction has the potential to engage, excite, and propel students forward. A strong writing curriculum is a key aspect in doing this. As a year like no other comes to a close, I hope you can use these six qualities to conduct a back-to-school writing check-up. More importantly, I hope that this reflection/check-up enables you to start this year with confidence and joy.

For more help with shaping your writing curriculum, check out “We Do” Writing, a new book by Leah Mermelstein.

Want more articles like this? Be sure to subscribe to our newsletters.

Plus, the best anchor charts for teaching writing.